Asian Art News, July – August 2009

Asian Art News, July – August 2009

The world of traditional Balinese dance is at the very heart of Indonesian artist Udin Antara’s oeuvre. His dancers link many threads of Balinese culture and the arts, as well as the natural beauty, mystery, and spirituality of Balinese life.

For centuries, the subject of Balinese lives has fascinated myriad artists. The island’s mystic beauty and exoticism have attracted a large number of foreign artists, including European painters such as Walter Spies, Le Mayeur de Merpres, Hans Snel, and the celebrated artist-mentor Arie Smit. These artists produced some of their best work while living in Bali. Bali’s rich cultures and age-old traditions have also provided idyllic backgrounds and inspiration for many local artists, dancers, and craftsmen. Art audiences often associate Balinese art with its traditional temple ceremonies, local market scenes, sacred religious characters, dancers and Balinese toiling on the rice fields. Such things have provided subject matter for classic drawings by I. Gusti Nyoman Lempad, Anak Agung Gde Sobrat, and Ida Bagus Made Widja, as well as prominent Indonesian modern masters such as Srihadi Soedarsono, Nyoman Gunarsa, and Dede Eri Supria who have expressed the essence of Balinese dancers in their own unique styles.

For a long time, many artists who prefer nomadic lifestyles have always regarded Bali as an artistic destination. The concept of traveling, exploring, and socializing with local Balinese lends their experience a romantic air, which appeals to the artists. Today, among the numerous artists who have found their niche in Bali are Zainuddin (Udin Antara), who was born in 1968, and is a native of Tulungaggung, East Java. After spending his school years in his hometown, Udin moved to Bali in the early 1990s. At an early age, his artistic talent was apparent. Without much guidance, he spent many hours creating freehand drawings. But his passion for painting eventually became the sole daily activity in his young life. However, coming from an impoverished family background, his family disapproved of his career choice as an artist. In order to support his family, Udin did various odd jobs before finally deciding to move to Bali to learn to be an artist.

From the outset, Udin’s journey to Bali was met with various obstacles: a lack of funds forced him to take up construction work during the day while he tried to paint at night. Not having a reputation as an artist did not help Udin to gain entry to Bali’s art galleries. Without any exposure, he was an unknown among innumerable other aspiring artists living in Bali. Through his many hardships, however, Udin did not lose sight of his original goal of becoming an artist. He sought assistance of more experienced senior artists. Through his acquaintance with several Balinese painters, Udin began to teach himself how to draw and paint in a proper way. Being a self-taught artist, he began painting still lifes. His endless experimentation with various techniques and colors helped Udin to discover and perfect his own style of expression.

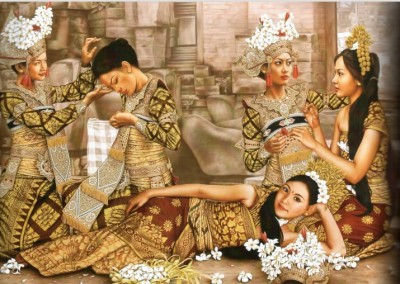

Living in Bali exposes Udin to many religious and cultural rituals. Like many artists before him, he is enamored with Bali’s performing arts, particularly Balinese dance. To Udin, dance is a celebration of life in which happiness is a direct reflection of his own artistic journey. He feels that depicting Legong dancers in their natural state is best expressed through his realist painting style, which has become his favorite subject. Coupled with his obsession in adding a realistic dimension to the dancing girls, Udin has chosen to highlight the girl’s interactions, dance preparations, and, most important, their costumes and accessories. Unlike other artists who express Legong dancers in richly painted colors, Udin instinctively style his images in brown color tones, thereby giving his paintings a sense of tranquil serenity. His audiences now associate the distinct style of sepia-toned Legong dancers with his work.

Of all the classical Balinese dances, Legong is perhaps most familiar to the general audiences and one of Bali’s most exquisite dances. “Leg” means “elegant movement,” accompanied by “gong” for the music. Legong’s popularity can be attributed to its exposure through various touring dance troupes and films. As one of the dances regarded as secular in nature, Legong is usually presented for entertainment. The Legong dance is also considered the oldest of the bali-balihan (non-religious) dances. Its origins can be traced to an early 19th century genealogical chronicle of the Sukawati princes. According to the story, Legong was created as the result of a vision that came to the ruling prince, I Dewa Agung Made Karna, renowned for his spiritual powers. While he was meditating at a temple near the village of Sukawati, the prince dreamed that he saw celestial maidens performing a dance while in a trance. They danced in colorful attire with golden headdresses. When he awoke, the prince requested the village craftsmen to make masks and create a dance that would resemble what he had seen in his dream. He also taught the villagers how to perform the divine music and dance. Another legend tells the story of King Dalem Ketut who brought nine masks of celestial maidens from Java. Though chronicle dates of both legends are inconsistent, the visions of both kings have become part of Balinese history. Thus, the dance, which was to be performed by young adolescent girls to symbolize divine celestial angels, was born.

Legong dance today is associated with the symbol of femininity. Performed for temple festivals, a group of three to five young talented dancers are usually chosen for their appearance. The young dancers adorn themselves in expensive silk costumes decorated with painted gold-leaf brocades and sparkling jewels. Aside from the heavily decorated costumes, the girls wear elaborate headdresses topped with flowers. The headdress is considered one of the holiest parts of the costumes. They are usually used to indicate characters and are given offerings before each performance. The Balinese believe that the leaves that stick out of the flowers act to calm performers and provide them with protective powers. Tiers of fresh frangipani flowers are structured to form “wire trees” that symbolize a mountain or the seats of Gods that move with every head movement. Since a large component of Balinese dance consists of costuming and make up, Udin feels that it is important for him to emphasize the special associations of the accessories typically worn by Legong dancers.

Udin has successfully painted hundreds of Legong dancers in various poses and stages of their preparations. He admits that Bali has given him priceless inspiration for his life’s journey. His dedication to the island he loves is apparent in his passion in observing the island’s arts, traditions, and cultures.

His recent collection of highly detailed work shows examples of that which constitutes the beauty of Legong dancers. In one naturalistic portrait, The Exotic Beauty of a Balinese Woman, Udin depicts his ideal wholesome Legong dancer. In creating a classically balanced picture, Udin demonstrates his skill in controlling the light. The woman in the foreground stands against the wall while in the background one glimpses steps leading to a temple. Udin’s distribution of light and darkness in the woman’s facial features allows viewers to feel the nuances of emotion in her expression. The contrast between the lightness of the background staircases and rich color of the woman’s painted silk and elaborate headdress stresses the three-dimensional nature of the work.

Aside from portraits, Udin is inclined to show the interaction between dancers. “The whole ritual of preparing for the dance is more important than depicting dancers on stage,” he says. “The process of the dance is fascinating because it allows me to observe the reality of Balinese life. This reality coincides with the naturalistic style of my works.”

In My Good Friend is Always Beautiful, a girl on the right can be seen in a dance pose while her companion is fixing her headdress. Both girls are seated in front of a temple. There is happiness in the faces of both girls. Udin once again emphasizes his control of lighting in the girls’ faces. The lightness of their faces contrasts with the dark shadow of their costumes, which results in the appearance of fresh-faced girls in the midst of their dance preparation. While the girls’ vivid expressions are lively, Udin also defines the roles of their ornaments and costumes. Using sharp lines, he makes repetitive round motifs to form patterns used in their chains and headdresses. The lines repetitive patterns result in precise intricately carved accessories. Acting as decorative ornaments, their two-dimensional nature emphasizes the essential flatness of the ornament’s surface.

In Dancing is My Life, Joy and Laughter before Performing, and The Value of Time, Udin succeeds in documenting the beauty of each realistic movement. The first work shows a smiling dancer practicing a dance pose. In Balinese dance there are many different hand gestures, eye movements, and stances. Audiences enjoy seeing how well a performer executes and interprets a dance. Udin is particularly observant in depicting the enthusiasm of dancers practicing.

For scenes that involve the dynamic interaction of the dancers, Udin is equally competent in creating larger compositions. Joy and Laughter before Performing, for example, shows five Balinese dancers teasing each other, sharing their joy with one another. The artist seems to understand the preciousness of the girls’ private time together before a performance. In this painting, the beauty of the girls in their rich costumes steals the show. However, viewers will soon notice that the shadows of the temple behind the girls serve a larger purpose in highlighting the girls’ roles in their upcoming performance.

Similarly, in his Value of Time, five girls are sitting in front of a temple. Here, the girls are engrossed in their preparation. Not seemingly ready, few of the girls are helping their dancing companion with their costumes and accessories. Unlike the previous work, the girls appear serious and anxious in completing their tasks. Since a performance is regarded as sacred affair, Balinese performers take their preparations seriously. Udin understands how traditional rituals play a significant part in Balinese lives and details this phenomenon in his works.

In his recent work, elegant temples and stairs are positioned to act as the background. These images provide a central focus to the sacredness in the tranquility of Balinese life. To achieve his dreamy effect, Udin skillfully applies his brushstrokes, effectively presenting the background images as distant shadows. In the foreground, viewers can see several girls sharing jokes and laughter while preparing for their performance. Udin repeatedly sets various temple scenes as the background while his richly costumed dancers occupy the central focus of the paintings. By differentiating the girls’ joyous and youthful expressions and the disappearing shadows of the temples, Udin manages to pull together opposing forces of the pictures’ surfaces and has balanced out their colors and value in accordance to his subjects. By relating various parts of his artistic elements cohesion is introduced. In repeating regular visual units, his works have a sense of harmony and balance, which results in pleasant images.

The integration of the arts into artist’s daily lives is very important in Balinese culture and the art of dance is interpreted in many ways. Indonesian modern master Srihadi Soedarsono is known for painting many different types of Indonesian dance. Known for his expressionistic style, Srihadi’s dancers do not represent physical reality. Instead, their mysterious forms guide viewers to experience a more emotional understanding of the works. On the other hand, Dede Eri Supria’s hyperrealist-style Balinese dancers have given him stature as the artist with an original and outstanding technique. Like both these artists who possess great artistic techniques, Udin has also made a mark in the Indonesian art scene with his naturalistic works. Udin has taken it a step further in his description of the dancers’ process, and capturing them as a moving picture would.

Among many accomplished artists, there are quiet artists who prefer to let pictures speak for themselves. The more experimental artists have successfully made a name for themselves in creating new ideas and theories of Balinese life. Yet, there are also those who are publicity shy but possess a deep conviction that their works have something to offer. Udin is one of those artists whose works give voice to his subjects. He is a serious artist whose passion and determination have helped hone his skills to be on par with his better-known counterparts. A selftaught artist of humble background, Udin’s achievements have been outstanding. His Bali is a visual treat. What is more important to Udin, however, is how he continues to explore the island’s beauty, its spiritual meaning, and the mystery of the sacredness of Balinese lives.